How To Repair Rusted Natural Gas Line

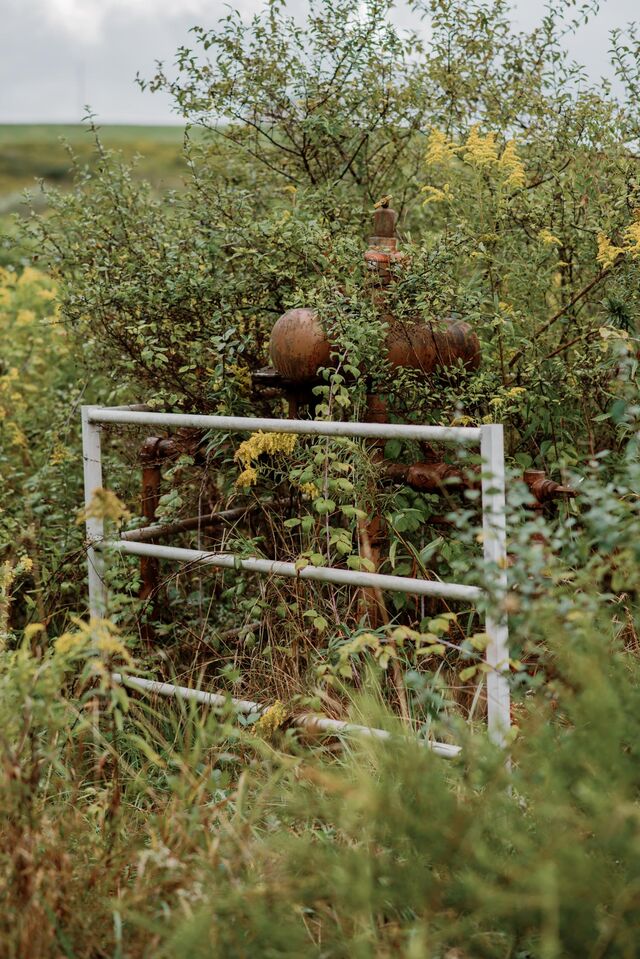

Decayed equipment serving 38-twelvemonth-sometime natural gas wells endemic by Diversified Energy in Ohio'southward Tri-Valley Wild animals Surface area. Videographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Greenish

An Empire of Dying Wells

Former oil and gas sites are a climate menace. Encounter the company that owns more of America'southward decaying wells than any other.

Outside of hunting flavor, few people visit the Tri-Valley Wildlife Area in the rolling hills of southeast Ohio. When a couple of Bloomberg Greenish reporters showed up on a muggy June morning, the only sounds were birdsongs and the whirring of our infrared photographic camera. Nosotros set out on foot and soon spotted the beginning of several rusty natural gas wells scattered across a wide meadow. Their storage tanks, half-covered with vines and brush, looked like the forgotten monuments of some lost civilization.

There are hundreds of thousands of such bedraggled oil and gas wells across the U.S., and for a long time few people paid them much listen. That changed over the by decade as scientists discovered the surprisingly large part they play in the climate crunch. Old wells tend to leak, and raw natural gas consists mostly of methane, which has far more than planet-warming power than carbon dioxide. That morning in Ohio we pointed our camera at busted pipes, rusted joints, and broken valves, and we saw the otherwise invisible greenhouse gas jetting out. A sour odour lingered in the air.

To Rusty Hutson, it smells like money.

Hutson is the founder and chief executive officeholder of one of the strangest companies always to hitting the American oil patch and the reason for our four-24-hour interval visit to the Appalachian region. While other oilmen focus on drilling the next gusher, Hutson buys used wells that generate just a trickle or nothing at all. Over the by four years his Diversified Free energy Co. has amassed about 69,000 wells, eclipsing Exxon Mobil Corp. to go the largest well owner in the country. Investors dear him. Since listing shares in 2017, Hutson's visitor has outperformed most every other U.S. oil and gas stock, swelling his personal stake to more than $xxx million.

U.Due south. Onshore Well Count

As of December. 31, 2020

Source: Most contempo company disclosures through U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program

But Diversified's breakneck growth has alarmed some regulators, landowner groups, and industry insiders, not to mention environmental advocates. Country laws require that every well be plugged with cement later it runs dry, an expensive and complicated chore. At the charge per unit Diversified is paying dividends to shareholders, some worry there will be nothing left when the bills come up due. If a company tin't come across its plugging obligations, that burden falls to the state, which means Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Westward Virginia could be stuck with a billion-dollar mess. "The model seems similar it's built on abandoning those assets," says Ted Boettner, who's studied abased wells at the Ohio River Valley Institute, a regional research organization. "It looks like a liability flop that's destined to explode."

Storylines: How Dying Gas Wells Are Making One Company Rich Video: Alan Jeffries

Storylines: How Dying Gas Wells Are Making One Company Rich Video: Alan Jeffries

Hutson says there's no cause for worry. He claims to be able to squeeze more than gas out of old wells than other companies can and proceed them going longer. On average, he figures his wells accept an additional 50 years in them, which means in that location's no hurry to start socking abroad money to plug them. It also means they could be spouting pollution long past 2050, the target engagement set by President Joe Biden for zeroing out emissions across the economy.

State regulators say Diversified hasn't broken any rules by building an empire of dying wells. Nor has information technology violated whatsoever restrictions on methane emissions, because none apply. Indeed, state and federal policies—from plugging regulations to taxation subsidies—encourage companies to do exactly what Diversified is doing: Keep almost dead assets on life back up every bit long as possible, no matter how much they may damage the planet.

A FLIR GF320 infrared camera can spot methane emissions normally invisible to the homo eye. Photographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Greenish

We decided to see for ourselves what Hutson's plans might mean for the climate past visiting 44 well sites owned by Diversified. We used state databases to find accessible wells on public land in 3 states. Then nosotros borrowed a $100,000 manufacture standard GF320 camera—designed to spot methane—from its manufacturer, Teledyne FLIR. I of united states got trained and certified to use it, and the other operated a handheld gas detector.

The results were worrisome. Nosotros found methane leaks at nigh of the places we visited. Some sites showed signs of maintenance in recent months, simply others looked more than or less abandoned. We saw access roads choked by vegetation, machinery buried under vines and weeds, oil dripping onto the ground, and steel doors rusted off their hinges. That'south not to say the wells were unattended. Mud wasps, spiders, mice, snails, and bees made their homes in them, and a porcupine napped under a alkali tank.

A Trip Through Appalachia on the Trail of Leaky Wells

Data: Well locations from country oil and gas records

Advocates for natural gas call information technology a cleaner fossil fuel because it releases about half the carbon dioxide as coal when burned. But there'southward a catch: Left unburned, natural gas consists by and large of methane, which is much better at trapping heat. Released into the air, a ton of marsh gas volition cause at least fourscore times more warming over the side by side 20 years than a ton of carbon dioxide. That's ane reason decision-making methane is among the cheapest and quickest ways to slow climatic change and limit the wildfires, rut waves, ascension seas, and droughts information technology's unleashing. According to ane contempo estimate, putting a chapeau on homo-acquired methane emissions could prevent as much as one-third of the warming expected in the next few decades.

A separator tank at a Diversified site in Pennsylvania. Right: The same tank viewed through the infrared camera reveals methane spewing into the air. Source: Bloomberg

Researchers around the earth are racing to reexamine the world's energy supply chain, finding where gas is leaking and showing what can exist done about it. Scientists are training infrared cameras on methane emissions in Texas oil fields, using satellites to spot them in Turkmenistan, and driving sensor-laden vehicles around city streets in kingdom of the netherlands. 1 trouble area they've identified: former wells that produce little or no salable gas.

Only nearly 3% of gas needs to escape on its journeying from wellhead to power plant to make it worse for the planet than coal. If a well is producing next to nada, even a small leak can put it over that threshold. "Marginal wells are emitting a very large proportion of the natural gas that they produce," says Amy Townsend-Small, an associate professor of environmental science at the University of Cincinnati. "Some marginal wells are emitting more natural gas than they produce."

Inspecting a Diversified natural gas well with a hand-held sniffer in West Virginia. Photographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Green

Townsend-Small is a co-author of a 2020 written report that examined old, low-producing oil and gas wells in Ohio, not far from Tri-Valley. She plant their emissions amounted to 21% of gas production. Two other peer-reviewed studies, using different measurement techniques and examining gas wells in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, found loss rates of 9% and 18%. None of the papers identified the well owners. Taken together, the research suggests that gas from old wells in Appalachia is one of the dirtiest components of the U.S. energy arrangement.

The damage doesn't cease when these wells stop producing. Some go on to leak methane for years if they're not properly plugged. Another paper estimated that as much as viii% of Pennsylvania's human-caused marsh gas emissions was coming from these inactive wells.

Our own survey wasn't scientific. But it provided some hints that bug noted by academic researchers, such as poor maintenance and frequent leaks, were besides present at Diversified'due south operations. At 59% of the sites we visited, emissions were significant plenty to cause our detector to sound a safety warning, indicating that the concentration of marsh gas most the instrument's sensor exceeded five,000 parts per million. Normal air contains about 2 parts. In a few cases the source appeared to exist a pneumatic controller designed to release gas, but the vast majority were leaks.

Methane leaks from the casing of a well called Wilson Coal Land No. 89. Diversified Energy later said it fixed the natural gas leak for $300. Photographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Dark-green

In a statement to Bloomberg Green, Diversified said that the wells we visited were "not representative of our entire portfolio" and that many had been neglected by previous owners and acquired simply recently. Some of the leaks we plant were tiny, the company added, and all of them were repaired inside a few weeks of our inquiries. The price for speedily fixing these wells, co-ordinate to Diversified, was less than $ninety on average. The company as well said it stock-still a leak in an underground pipeline in West Virginia subsequently we reported finding a high concentration of gas nearby.

Diversified said that it's committed to reducing methane emissions across its operations and that information technology's investing in training and equipment to help field personnel find leaks. As for the academic studies showing high emissions rates in the region'due south old wells, Diversified questioned their accurateness and said its ain wells are better maintained than those of other companies, with staff visiting wells once a month on average. "Nosotros firmly believe that we are the all-time custodian of these wells," the company said.

No one, including Diversified executives, knows how much marsh gas is really leaking. Unlike carbon emissions, which are commonly a function of intentional fuel use, methane emissions are oft inadvertent and intermittent. That makes them almost impossible to measure comprehensively across thousands of locations. Similar most oil and gas producers, Diversified estimates emissions using formulas, most of them adult by the U.Southward. Environmental Protection Agency, that assign a theoretical leak charge per unit to each valve, connector, and tank. For 2020, Diversified told investors those numbers added up to about 38,000 tons of methane, or less than ane% of its gas production. The formulas don't accept into account the historic period or condition of hardware or whether whatever efforts were made to fix leaks.

A natural gas well in Ohio shrouded past shrubs. Photographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Light-green

Researchers say the actual measurements they get in the field are often wildly different from those predicted past formulas. The study of wells in West Virginia establish emissions rates more than than seven times EPA numbers.

In February, Diversified told Pennsylvania regulators it had self-inspected i,412 of its least productive wells in the country and reported that none was leaking gas. We visited three of those wells in June. Two were leaking.

Hutson Photographer: Billy Brown

Hutson, 52, grew up in the tiny Westward Virginia river boondocks of Lumberport, where his great-grandfather, granddad, and father, Rusty Sr., all worked for the local gas visitor. "There were two kinds of people—yous either worked in coal, or you worked in oil and gas," Hutson, who declined to exist interviewed for this story, told BBC News concluding yr, recounting his visitor's origins. "It was a generational affair. If your dad and grandfather did it for a living, then you lot did it." Instead, Hutson became the start in his family to graduate from higher, earning an accounting degree and pursuing a finance career out of state.

Past his early 30s, while working at a depository financial institution in Birmingham, Ala., Hutson turned back to the family business concern. He borrowed against his house to buy a few quondam gas wells near where he grew upward. And so he bought several more. Within a few years he quit finance to focus on gas full fourth dimension. He set up company headquarters near his home in Birmingham while working closely with his father in Lumberport.

The fracking revolution in the early 2000s created opportunity. Companies were pouring money into new drilling techniques to unlock vast amounts of oil and gas from shale fields. When they lost involvement in their older, less productive conventional wells, Hutson was there to buy. Past 2017 he'd amassed vii,500 wells. That February he floated the visitor'south shares on AIM, a lightly regulated arm of the London Stock Commutation for modest companies.

Hutson, who has a square jaw and advisedly parted gray hair, started actualization in videos on stock-promotion websites, talking up his company's prospects. He unveiled a Diversified plan called Smarter Well Management, a sort of Fountain of Youth for decrepit gas wells. Over time, wells tend to bring forth less and less oil and gas until they're finally spent. Hutson said Diversified had developed a system to deadening the reject and fifty-fifty resurrect wells that others had left for expressionless.

Sometimes the nearly assisting reason to extend the life of an old well isn't the extra oil or gas that comes out. It'south the delay in the date when a well has to exist plugged. When companies tell investors how much they expect to spend on retiring wells, they discount it by how far abroad that day of reckoning is. On the books, a 50-twelvemonth timeline makes Hutson'southward cost almost disappear.

Because it plugs so many wells and keeps much of the work in-house, Diversified says it tin retire wells for under $25,000, less than industry norms. Thanks to that, and the unusually long time horizon, Diversified frequently records its plugging liabilities at a fraction of what other companies would. In 2018 the company bought a portfolio of wells from CNX Resource Corp. CNX had pegged its cleanup liability at $197 million. Diversified put the liability for the same wells at merely $14 million.

A tank in Ohio'due south Tri-Valley Wildlife Area. Photographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Green

This may explicate why Diversified frequently determines the wells it's buying are worth far more than what it paid—so much and then that it books the divergence as profit upfront. Since 2014 the corporeality Diversified has fabricated from these accounting gains is more than its cumulative reported turn a profit. In its argument the company noted its books are reviewed by outside engineers too as independent auditors at PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Afterwards going public, Hutson accelerated his buying spree. By last yr he owned well-nigh 1 in 5 wells across Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Tom Loughrey, an oil and gas data annotator in Chapel Colina, N.C., remembers the twenty-four hour period in 2019 when someone on a phone phone call mentioned a new visitor that had more wells than anyone else. "I've worked in upstream oil and gas finance and investing since 1998," he says. "I had never heard of the visitor before."

Loughrey was intrigued. Could Diversified really make money from such geriatric wells? In a web log post final year, he wrote that he analyzed 37,000 Diversified wells and wasn't optimistic. Nigh half of the ones he looked at were producing less than 15,000 cubic feet a day, he wrote, "which in this cost environment will barely buy you luncheon."

"Every oilman since the beginning of time has wanted to buy proved, producing assets," Loughrey says. "Why is information technology that Diversified is the only company that's able to pull this off this decade and exist successful with information technology? Why is ane visitor basically beating the market? It boggles my mind."

The Methyl hydride Menace

Read more about the supercharged gas that could turn the tide of global warming.

American oil executives talk about a food chain in their industry. Large, well-capitalized companies tend to be the ones to drill wells and harvest the outset years' production. As output tapers, wells typically alter easily a few times, then spend their golden years with a smaller, more financially shaky visitor. If that company goes broke, there's no coin to plug the well. In most states, previous owners aren't liable. That helps explicate how an industry that created some of the biggest fortunes and most valuable companies has likewise produced hundreds of thousands of orphaned wells, with no owner around to clean them up. The Interstate Oil & Gas Compact Committee estimates the number across the U.South. may be as high equally 800,000. In August the U.S. Senate approved an infrastructure beak that includes $4.7 billion to begin tackling the problem.

Hutson's company represents a new link in the chain. Many of his wells were once owned by the biggest explorers, such as Exxon Mobil and Chevron. But rather than scattering among hundreds of pocket-sized-time operators, the wells are at present catastrophe upwardly with him. That'due south smashing if Diversified tin can keep its promises. Information technology too concentrates the risk if something goes wrong.

The Diversified takeovers prepare off alarms. In 2018 a grouping of Westward Virginia landowners sought to block the transfer of iii,865 wells, warning of "i of the most, if not the most, widespread environmental and property-rights disasters ever in Due west Virginia."

Some regulators were worried, too, but they had little leverage. Although well owners must postal service bonds to cover cleanup costs, the amounts required are then modest they're almost meaningless. Regulators have limited powers to block transfers to a new owner. The Due west Virginia transfers were approved afterward the state denied the landowners' request for a hearing.

In Pennsylvania, Scott Perry, the state'due south chief oil and gas regulator, told an advisory council in 2019 he had "considerable concern" that so many wells had been bought by the same company, co-ordinate to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. "No one broke the police force by selling wells to that visitor, and they didn't suspension the law by buying them," he said at the meeting. "But the police is weak."

Thousands of wells Diversified bought were producing zero at all, meaning they were already out of compliance. State laws require nonproductive wells to be plugged promptly, and then they don't endanger groundwater or grab burn. But enforcing this law is hard. Regulators worry that if they push companies also hard, it can cause financial distress and reduce the chances that annihilation will be plugged. "If the brunt is and so high to plug a well, so a company may not be able to do it, and you've defeated the purpose," says Eric Vendel, chief of Ohio'due south Partition of Oil and Gas Resources Management. That concern was specially acute for Diversified, which was juggling an unprecedented number of idle wells in multiple states.

A metal door leans against natural gas equipment in Ohio. Photographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Greenish

Instead, four states—Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and W Virginia—cutting deals that requite Diversified virtually a decade or more than to bring roughly iii,000 idle wells into compliance. If the visitor revives enough of those wells, it'due south required to plug only xx unsalvageable ones a year in each of the four states. At that step it would take about 750 years for Diversified to plug everything it currently owns in the region.

State officials say the visitor has kept up its stop of the bargain so far. Last year, Diversified said, it plugged 92 wells, a dozen more than than required. The company said its pace beats whatsoever other visitor in Appalachia, an assertion that couldn't be independently confirmed. It also reported reviving production at hundreds of idle wells, which ways it's off the hook from retiring them anytime soon. U.s.a. don't accept enough inspectors to verify these production claims, so they generally rely on what Diversified tells them.

An incident in Ohio shows the risk of that approach. In 2019, Diversified told land officials it had revived a well in Trumbull County, squeezing a modest amount of gas from a site that had produced nothing the previous year. That put the well dorsum into compliance with country law. Simply when a land inspector visited the following June, she institute the site idle, co-ordinate to a report she filed. A field employee explained that the well was filled with water and hadn't produced anything the year before, contradicting what the company had claimed. Diversified said any misreporting wasn't intentional.

Equally president of the W Virginia Royalty Owners Association, Tom Huber represents individuals who share in the profits of oil and gas production on private land. He has every reason to cheer for a company that says information technology can boost output and go along wells going longer—the more than production, the bigger the payments to his members. "I want Rusty and Diversified to make a bunch of money and to stay in business l years," Huber says. But he fears Diversified won't exist able to meet its obligations, leaving a mess for taxpayers to clean upward. "I hate to audio pessimistic about it," he says, "but I'm pessimistic."

Amy Townsend-Minor (right), an associate professor of environmental science at the University of Cincinnati, is one of a growing tribe of methane hunters. She uses an Indaco Howdy-Catamenia Sampler (left) to measure methane escaping from a leaking natural gas well in Westward Virginia. Photographer: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Green

On the concluding day of our trip, we met upwardly with Townsend-Small in W Virginia. She's one of a growing tribe of methane hunters who venture to oil fields from Romania to United mexican states to document emissions of the greenhouse gas. She arrived with a carload of gear and cheerful advice on ticks, poison ivy, flat tires, and other hazards of fieldwork. Her goal was to measure the amount of emissions at a few wells, something our equipment couldn't do.

We took Townsend-Small to three wells we'd identified as leakers. At each, she used a handheld detector to find where gas was escaping. So she lugged a metal suitcase to the site and opened it, revealing a contraption called an Indaco Hi-Catamenia Sampler. It looked like a relic from a 1950s sci-fi movie, with a chrome control panel and a curlicue of plastic hoses. She held ane hose nearly the leak after roofing the expanse with plastic sheeting. The car's display console showed the concentration of methane in the sample as well equally the charge per unit of menstruum. That allowed her to calculate the amount of methane pouring out.

Townsend-Small found emissions of 38, 50, and 91 grams an hour at the wells she measured. If those rates continued over the course of a twelvemonth, the three wells would cause the warming equivalent of 134 tons of carbon dioxide. Diversified said those amounts aren't inconsistent with the emissions figures information technology already discloses to investors.

An employee had visited the biggest leaker we measured, Wilson Coal Land No. 89, a few days earlier we showed up and hadn't noticed any problems, the company said. After our inquiry, Diversified said it sent someone dorsum to brand a $300 repair. West Virginia records show No. 89 produced only a trickle of salable gas terminal yr—almost viii,000 cubic feet. That means information technology may have been leaking six times what it produced for sale, making its gas a far more potent warming amanuensis than coal.

No. 89 was drilled in 1964 and passed through a handful of owners before Diversified bought it final year from a pocket-sized Colorado company. The gas it produced in 2020 would have been worth about $25 wholesale. It'south difficult to imagine how a well like that could ever be profitable once more.

Keeping a well like No. 89 going makes more than sense later on considering the government policies that shape Diversified's business organisation. Past not requiring drillers to postal service cleanup costs upfront, state laws incentivize companies to delay plugging equally long as they tin can. Marginal well owners likewise collect a federal tax credit, meant to support jobs in the oil and gas industry when prices fall below a certain level. Last year, Diversified reported an $fourscore million benefit from the subsidy, or most i-5th of what it got from selling oil and gas.

Diversified gas wells in W Virginia. Wilson Coal Land No. 89 (top row, 2nd from left) may have been leaking 6 times as much gas as it produced for sale last twelvemonth. Lensman: Kristian Thacker for Bloomberg Green

In West Virginia there's an additional benefit. Last year the legislature cut the severance revenue enhancement on the lowest-producing wells in half. Diversified, past far the biggest beneficiary of the cut, told investors it "engaged with state regulators in West Virginia to help craft" the nib, which also directs acquirement toward plugging orphaned wells.

In a land that'southward been losing coal jobs and was mostly left out of the fracking smash, Hutson is burnishing his visitor's image equally a local success story. Diversified, which now employs more than 1,000 people, recently became the "official energy partner" of West Virginia University'south Mountaineers, and Hutson's proper name graces a laboratory at Fairmont State University, his alma mater. The country has been good to him, too. Not long after passing the taxation pause for low-producing wells, information technology allowed Diversified to experiment with a less expensive process for plugging wells than country regulations require.

The $4.seven billion measure working its way through Congress would help states bargain with thousands of wells that must be plugged at taxpayer expense because owners disappeared or went belly upward. While the spending would reduce methane emissions and create oilfield jobs, it doesn't address the reason those wells were orphaned to begin with: state laws that fail to ensure the industry cleans up its own messes.

Although some ecology agencies have begun regulating marsh gas emissions, they've shied away from targeting the kind of older, depression-producing properties that Diversified owns. Trade groups argue that the price of inspection would make these wells unprofitable and could impale local jobs and hurt minor businesses. The EPA, which issued a methyl hydride regulation for new wells in 2016, is now crafting a rule for older wells but hasn't said how it will treat depression producers. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania exempted low-producing wells when it proposed a statewide marsh gas rule last year, sparing more 99% of Diversified'southward holdings in the state.

After years of focusing on his native region, Hutson wants to replicate his strategy elsewhere, amassing quondam and overlooked wells on the inexpensive. His current prospect is a patch of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and eastern Texas, where he lined upward four acquisitions this year. "We have a lot of opportunity in forepart of us," he told investors in July. The visitor was recently promoted to the LSE'southward main market, where the biggest companies merchandise.

In Appalachia the rust accumulates. State records show that more than 1 in x of Hutson'south wells there aren't producing anything at all. Amid them is one known every bit Fee A 36, nigh hidden past weeds in a forest in cardinal Pennsylvania. Drilled during Globe War II, Fee A 36 in one case belonged to Chevron Corp., but past the time the well stopped producing gas in 1998, it had already been through several different owners. It'due south no longer fifty-fifty connected to a gathering line. A rusty pipage leading from the wellhead ends in an open shaft, where our camera recorded methane trickling by ii large bees sheltering inside.

Even Diversified acknowledges this well tin't be resurrected. Just its deal with Pennsylvania requires it to plug but 20 wells a year, and there are hundreds of wells to retire. Fee A 36 will have to wait its plough.

More On Bloomberg

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/features/diversified-energy-natural-gas-wells-methane-leaks-2021/

Posted by: ouelletteglikeels.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Repair Rusted Natural Gas Line"

Post a Comment